Ray Larribas

WWII Hero, Former POW, my grandfather ...

In honor of the lifetime of service Sgt. Ray Larribas devoted to his country, and now so energetically gives voluntarily to assist our nation's veterans, we highlight a short story written by Angie S. Lopez and include some personal and family memories of a true American hero.

Ray Larribas: WWII Hero, Former POW, my grandfather

Ray Larribas, an energetic man, of average height and build, roams about the V.A. Hospital in Albuquerque helping his comrades-in-arms. Whenever there is a veteran in need or a veteran's function, one will often meet up with Ray Larribas. He was roaming when I met him. He escorted me into the POW office and made me feel at ease by showing his concern for my comfort. He'd always helped those who needed him. With difficulty, he told me his battle story.

509th Parachute Infantry Battalion

Ray is an only child. He was born in the area of Albuquerque, New Mexico called Martineztown, to Frank and Isabel. Ray attended Longfellow and Lincoln Jr. High School, then enlisted in the U.S. Army on December 2, 1940, where he received his G.E.D. and continued his education. Ray was with the First Cavalry in Ft. Bliss, Texas, for one year when World War II broke out and the Army requested volunteer paratroops to go to Europe. Ray volunteered for airborne duty. He was then sent to Ft. Benning, Georgia, where he passed all the tests and began his life as a full-fledged paratrooper. He was part of the First Airborne unit sent to Europe.

82nd Airborne Division — All American

"There were five of us on a mission, operating behind the line as a machine gun group. We were captured on February 29, 1944, right after the beach landing on Ansio in Italy, near Rome. Approximately fifty-three days after the beach landing, the five of us were completely surrounded. We'd been looking for German strength — and we found it.

"The was no place to go, neither forward nor backward. I remember one guy from Ohio, his name was Pyle, about twenty years old. He and I were the only ones left alive. A short time later, Pyle was shot in the head, killed by a sniper.

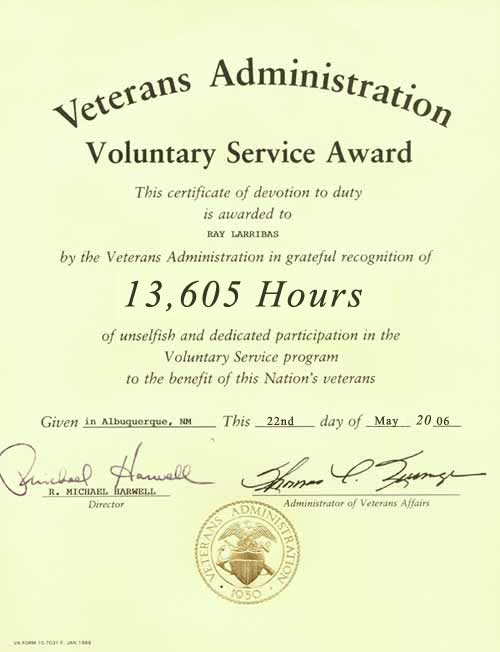

VA Voluntary Service Award

"Out of the five on this mission, I was the only one to survive. At that point, there was nothing I could do but surrender or be shot. I cared less at that time whether I was killed or not. I had nothing to fight with. I was exhausted, hungry, and there wasn't much fight left in me. It was raining that day, so everything was muddy. Our weapons had been destroyed, I was sick from phosphorus burns on my body, and it had been a terrifying day.

"When I was captured, the Germans had managed to capture others

in the vicinity. These were guys from a ranger and an infantry outfit. When

the enemy felt they'd captured enough of us, they gathered us together and

marched us to a nearby camp in Italy. I forget the name of the camp, but

they threw us in for about five or six days without food, water, or medication.

Ray Marching in Washington, D.C. in 1994

"We were later transferred by train to Stalag 7-A in Munich, Austria, where they transported all personnel captured in the Italian campaign. There were approximately fifty to a boxcar. Again with no food or water, only a honey bucket, which meant we were in very unsanitary conditions. It took a good three days to get to Stalag 7-A. Once we got there, we were interrogated together.

"British, Americans, some soldiers from India, and some Moroccan troops were together for a period of seven months. After seven months we were then segregated by rank. The privates were sent to commando camps where they could work them on farms or ranches. The officers and NCOs were sent to different areas in Germany. I was sent with the NCOs to Frankfurt, Germany on the Marne. I'm not exactly sure where the officers were sent to but I believe it might have been near the Baltic Sea. We were segregated to limit communications among the American soldiers.

Ray Serving in Morocco after WWII

"After Stalag 7-A, I was shipped to Stalag 3-B in Frankfurt, where I was kept for the remainder of my captivity, a total of thirteen months. While I was there, the food I was given was inadequate. We didn't have very much and what we had consisted of a bowl of soup, a cup of weak tea, coffee or whatever you might want to call it. Sometimes we would have a loaf of break for twenty guys. No one got much of it. If you were lucky, you'd get a very small slice.

"Of course, there were ways in trying to get a little more to eat, if you worked on a detail. As NCOs, we were not required to work because

of the Geneva Convention, but NCOs could if they wanted to.

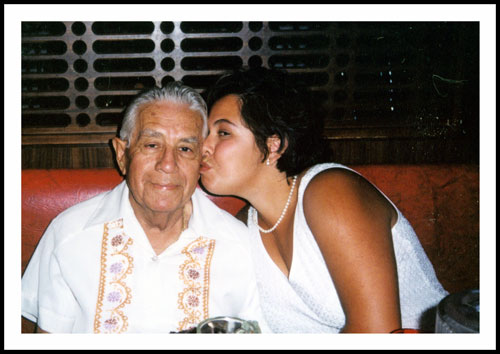

My grandfather and I on my wedding day

July 17, 1998

"The enemy wanted us to volunteer to repair the railroad or work the farms, but we said, 'NO!' We would rather starve to death than help them repair whatever was destroyed so they could continue the war. We told them, 'No, we won't help you. You have our other privates who are entitled to work according to the Geneva Convention.' You se, if we helped the Germans, as NCOs, we'd not only be prolonging the war, we'd be subject to court-martial after the war. So we stuck by our code. We would not help the enemy. How could we?

"All around us we saw destruction caused not only by weapons of every size and power, but also by disease, hunger, thirst, and fatigue. From every vantage point, the rubble and dead bodies surrounded those who came into the midst of the red demon of war torn Italy and Germany.

"The first prison camp was full of British, Americans, Indian soldiers from India and Moroccans. We were segregated and I remember that the worst thing for all of us was that there was no food or medication. We were guarded day and night, forced to stay where we were told. Oh, you could go outside in the daytime and exercise a bit, but you had to be inside the barracks before sundown. If you were caught outside the barracks after dark, you would be punished.

"One of the forms of punishment was isolation. The Germans would lock you up in a separate cell for an indefinite amount of time, segregated from everyone else. Not many of us were ever outside after dark, there was just no advantage in that form of resistance. Besides, the Germans might decide to start shooting.

"No one really wanted those Germans to take a potshot at us, so, mainly, we stayed where we were. Oh, there were some who tried to go through the fence. They didn't make it. They were shot right on the spot.

"There were about 200-300 men at this particular camp. After we were transferred to Frankfurt, there were 5,000 of us, Americans, Russians, Italians, and Polish soldiers, mostly NCOs. There were so many of us at the Frankfurt camp that some of us were sometimes able to sneak out underneath the fence and search for food. I was one of the principal ones who would try to bribe the guard with a cigarette or whatever we had. We were sometimes able to get to the other compound nearby, where we might be able to scrounge some food from the Italians, Russians, and Polish POW's. Close to us there was also a Russian women's camp where they were very badly abused. Because they had no food to trade for survival, they would receive a slice of black bread whenever the German guards decided they wanted a woman. Invariably, these women became pregnant.

"There was so much that went on in these camps that sometimes it's hard to describe. I remember that I was caught three times trying to sneak out of camp to look for food. When we were caught, they would put us in an isolated room, separate from the rest of the guys, for one or two weeks. Even though we'd get caught and punished, we'd be back doing the same thing as soon as we got out of solitary.

"Finally, the day came when the allies were moving in from on side, the Americans from another side, and Russians from yet another side. One morning we woke up and the enemy told us they were going to march us out toward Berlin so we couldn't be liberated by our allies. We walked that march for about eight days in the cold and the dead of winter. You could hardly call what we had on good clothes or shoes. We didn't have much of anything to eat, they might give us a piece of black bread, but sometimes we were able to sneak out to a nearby farm to steal some food. We did our best.

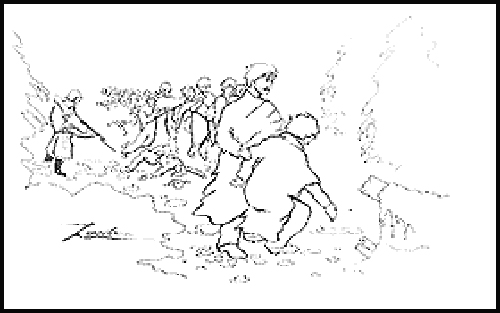

Captured behind enemy lines

illustration by Ray's son, Gerald

"Those who couldn't keep up the march were either shot on the spot or had the German dogs set on them. A lot of the men didn't make it. Everyone was so weak it was almost impossible to carry anyone, but many of us tried.

"I personally carried many who were weaker than I, but as the march continued we all just got weaker and weaker. There were many who had been captured in North Africa and had been prisoners for two, two and a half years already. Those guys were in pretty bad shape and most of them didn't make it.

"Throughout captivity, we were infested with all kinds of diseases. There was dysentery, asthmatic problems, heart problems, malaria, and all kinds of tropical diseases. Our sleeping quarters were also very bad. We had no heat. Our furnishings consisted of a small blanket and a straw mattress about an inch thick. It was very uncomfortable. I knew we were not there to be comforted, but that knowledge didn't make a very, very had situation any easier.

"It took about eight days to get to Luckenwalde. We marched by day and slept at night. At Luckenwalde they put us in this huge tent. About the second day we were there, they gave us these Red Cross boxes containing marmalade, chocolate candies, and other little goodies. There was one box per four or five men and when we received them, we tore into them — and got sicker than dogs.

"We supposed that these packages had been confiscated by the Germans, and had no idea why they'd given them to us. The boxes must have been two or three years old, but we didn't care,we tore into them like pigs. Afterwards, the dysentery almost did us all in. As we were all thrown into this tent together, you can imagine everyone crawling over each other trying to find a place to use the bathroom.

"About the third day in that camp I started thinking of what was going to happen to me if I stayed there. I knew this was the worst place I could be, so one day I told this guy from Michigan that I was going to get the hell out. I asked if he wanted to come with me, and he asked where we would go. I told him I didn't know or give a damn where I went. I didn't even care if I was killed. I just wanted out. I told this guy that I thought I could find the American lines and he agreed to come with me.

"We left that night by jumping over the fence. The Germans didn't catch us, so we kept on moving. We'd walk mostly at night, but sometimes we had a chance to walk in the daytime. Sometimes we would receive help from some civilians. I guess by that time the German civilians had a pretty good idea that the Americans would soon win the war, so they agreed to help us. I asked if they knew where the American lines were and was told that they were near the Elbe River, a two or three day walk. We continued our journey and arrived at the American lines on the third day. During our trek, we were always hungry, thirsty,very tired and very afraid that we'd be captured again and shot. But, we weren't recaptured or shot. Instead, we crossed over to the Americans. Boy! That was a great feeling. The American G.I.'s welcomed us and we felt great.

"We were taken to a German Air Force base at Bitburg, Germany, bedded down, given food, medication, and new clothes. A lot of the guys were sent there for processing to go back to the States. From Bitburg, I was flown to France, where they gave us a medical checkup of sorts, then flown again and this time to New York. We were again issued new clothes, given medical attention, and ordered on a two month convalescent leave. I went home for those two months, until I had to report to Santa Barbara, California for two weeks more of medical check-ups. After the two weeks in the hospital we were then discharged and told we could go home and pickup our lives again."

The Larribas Family

On December 3, 1945, three months after Ray Larribas was discharged, he married Maria Belen (Bea). They have six children: Bonnie, David, Gerald, Celia, Rosemarie, and John. Ray's son David served one year in Vietnam with the 101st Airborne with a total of three years in the U.S. Army.

Ray served a total of 22 years in the U.S. Military. Five years in the U.S. Army and was discharged on September 8, 1945 then re-enlisted in the U.S. Air Force until 1963, as a A.F.S.C. (Air Force Specialty Code-1383) fire protection supervisor for crash and rescue. After 22 years of service he went to work for Sandia Labs in Albuquerque and retired after sixteen years service.

Ray belongs to Albuquerque Chapter #1 of Ex-POWs where his is a sergeant-at-arms. He is currently working as a volunteer POW service officer at the V.A. Hospital in Albuquerque. He says:

"All I want to do is assist those disabled POWs who might need my help, regardless of which war. My main objective is to help all POWs."

SOURCE: Lopez, Angie S., Blessed Are The Soldiers, Sandia Publishing Company, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1990.